By Moses Ngware, Head of Education Research Program, APHRC via Daily Nation

Is education a public good and can it be sold at the market place using the “willing seller willing buyer” principle? Did you go to a public or private primary school? Whichever is the case, who paid for your education and was it a choice? It is important to ask yourself these questions because you, like other Kenyans, pay taxes and hence expect to benefit from public services.

Since you have to “buy’’ education in an open but monopolised market, there are chances that you can be exploited either through high fees or low quality education. Although the government has made significant steps in the sector through Free Primary Education (FPE), a considerable proportion of poor Kenyans in urban areas hardly benefit from the programme.

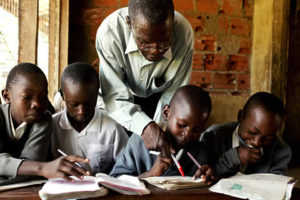

Research by the African Population and Health Research Centre shows that more than 60 per cent of children in Nairobi’s slums attend non-government schools that charge low fees. You may be surprised to know the extent of social injustice, and the emergence of strategically positioned profit-making entities in Nairobi slums. Most children in urban slums pay for their primary and secondary education, without receiving a cent from the FPE.

On the other hand, public funds are allocated to the programme to subsidise education for the children. The concern here is not about the rich enjoying FPE subsidies. They are entitled to them. What is worrying is that the poor living in urban slums hardly have access to the subsidies. Surprisingly, the same system expects a child who attended school without FPE support to be a patriotic and law-abiding citizen.

This social injustice is made worse by the quota system of admission to public secondary schools, whose fees are subsidised by the government. Children from slums such as Korogocho and Viwandani who attend private primary schools that charge low fees are placed in the same category of admission to public secondary schools with those from Muthaiga, Runda, Kilimani and Lavington. By so doing, their chances of

being admitted to good public secondary schools diminish. Better performers from the upmarket areas will take up most of the Form One places in public secondary schools set aside for private primary schools.

It is important to note that the children from the upmarket areas also deserve the places. At the same time, the provision of education by private players is commendable as long as it helps to meet the needs of Kenyans. Private providers of education in urban slums are diverse and driven by different motives such as profit, philanthropy and faith. The most callous of these individuals are the profiteers. They promise low school fees, good quality education, flexibility in the payment of fees and good teachers.

Unfortunately, information on the profiteers is scant as they operate in a closed system, perhaps to hide professional malpractices, including drilling of learners so that they can pass examinations. What is amazing is the speed at which some international government organisations have stepped in to support such profiteers. The profiteers’ education models are considered effective. Such models will hardly “fail” during the trial phase yet in real life, they are nothing more than global experiments conducted in Africa. Africans are made to believe that they are strategies to improve education.

What is even intriguing is that a country that adopts such a model — privatisation of education in poor neighbourhoods — can easily pass the “good investment climate test” and attract international investors. What then can the Ministry of Education do to curb this social injustice? A number of home-grown

strategies can be put in place. The so-called low-fee schools should be brought under closer watch of the Ministry. They should be provided with FPE capitation targeting the child. It is prudent to know what goes on in the schools and inform the public about it.

It is now more than 10 years since FPE was started and there cannot be any good explanation why the poor should not have access to the programme. If some children continue to be locked out of the programme, the government will be breeding individuals who are disoriented as they feel discriminated against.