Africa is experiencing a nutritional transition. Dietary patterns are changing as globalization contributes to food environments that are teeming with tempting but unhealthy choices that were unavailable a few decades ago. Combined with the rapid urbanization across the continent from rural to urban areas where such foods are cheap and available on every corner means that it is easier than ever to overconsume unhealthy foods that are high-calorie and low in nutrients. Habitually filling up on processed, nutrient-poor foods can lead to diet-related non-communicable diseases. Non-communicable diseases, or NCDs include medical conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and asthma.

According to the World Health Organization, deaths from NCDs are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries and rates are steadily rising. Unfortunately, Kenya exemplifies this trend; NCDs account for a third of all deaths and half of all hospital admissions. Being above a healthy weight – among the top risk factors for developing an NCD – is especially a risk among women. Overweight and obesity among women in Kenya has risen about 10-fold (25% to 33%) from 2008 to 2014 with roughly two in three women aged 40-60 years living in urban areas of the country considered to be overweight.

NCDs account for a third of all deaths and half of all hospital admissions in Kenya. But government actions can help stem the tide.

New joint research from APHRC, the University of Ghana, and the University of Sheffield is trying to find systematic, policy-level ways for governments to try and curb the trend in overweight and obesity, both because of the public health concern and the financial toll that diet-related NCDs take on a population.

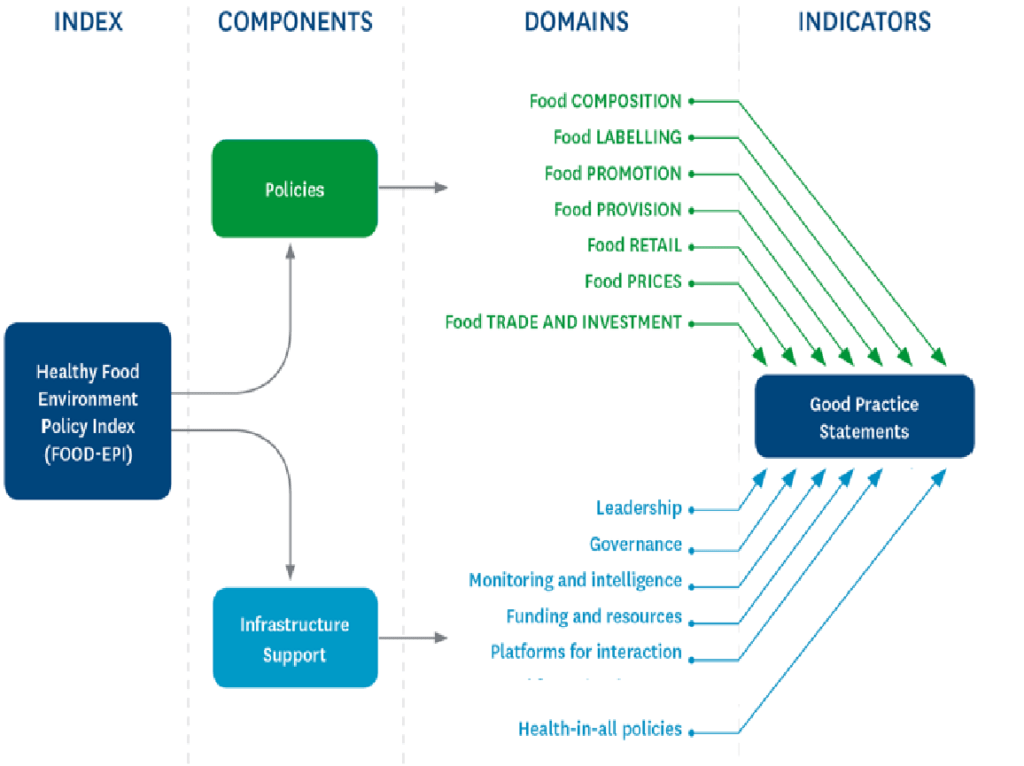

To that end, more than a dozen experts in health, nutrition, and NCDs gathered in Nairobi in July 2018 to participate in a workshop to review evidence and propose priority actions using a tool developed by the International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-Communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) process. INFORMAS developed a healthy food environment policy index (Food-EPI) tool to help assess what governments are doing to make it easier for us to eat or drink healthily, such as improving food labelling, restricting adverts about processed foods or controlling the price of unhealthy or healthy foods through taxes or subsidies. The Nairobi policy workshop is one component of the work to expand the body of evidence on dietary transitions in African cities.

APHRC’s Milka Njeri compiled information on the extent to which policies exist in Kenya and are implemented across 13 domains ranging from food promotion to labeling, to policies on food trade, to infrastructure, governance and health. Examples included government actions such as earmarking funding for implementation.

The Healthy Food Environment Policy Index includes 13 domains under which experts reviewed and ranked policies and proposed government actions. (Figure source: www.informas.org)

The assembled experts were first asked to rate Kenya’s implementation of these policies in relation to international best practices, using a scale from very low or no progress to very good or excellent progress. Second, they scored how far along they believed implementation currently exists, ranging from early to late stages of progress. Where there are no existing policies or no evidence of policy action or both, participants selected “cannot rate.”

For example, the group ranked Kenya’s progress on food labelling against the good practice indicator of having standard and regulated food labelling that allows consumers to easily assess how healthy a packaged food item is. While there is a policy in Kenya that packaged foods must declare their levels of trans fatty acids, as these are strongly linked to heart disease, evidence shows there are currently no requirements for a single, consistent, easily understood, evidence-informed front-of-pack supplementary nutrition information label. The experts compared this to international best practices, including from Ecuador, where all packaged foods must display a “traffic light” label to quickly, clearly communicate levels of fats, sugar and salt using color coding – red (high), amber (medium) or green (low).

The final step was for the experts to rank their collectively proposed government actions first in terms of importance, or the extent of significance of anticipated value of the action, and then in terms of achievability, or how easily the action might be accomplished given political, budgetary and social realities. Analysis is already underway, and the results will be used to benchmark and continue to monitor government policies to improve food environments to increase their accountability and action.

Kenya is only the second country in Africa (after South Africa) to conduct the Food-EPI policy benchmarking. The research team adapted the model slightly to pilot a new element to reflect emerging evidence showing that infants who are breastfed have better protection against NCDs later in life.

The same Food-EPI policy benchmarking will be carried out in Accra under leadership of APHRC’s counterparts at the University of Ghana later this year. As the number of participating countries increases, it is hoped that the pool of policy best practices will deepen, and hopefully, strengthen.