CONTRIBUTORS

Nelson Muhia

Research Officer

International Day of Women and Girls in Science

Participation of Female Learners and Teachers in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) in Kenya.

The International Day of Women and Girls in Science is a rallying call to promote the participation of women and girls in science but also an opportunity to take stock of the progress made so far. Several global and national initiatives have been put in place to ensure that women and girls are empowered and have the opportunity to reach their full potential. For instance, Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 4 and 5 aim to eradicate gender inequalities in women and girls’ participation in education, leadership, and decision-making processes. Closer home, the 2015 Education and Training Sector Gender Policy endorses the participation of women and girls in science by reducing gender inequalities in access, participation, and achievement at all levels of education and improving their participation in research and STEM subjects and courses.

Whereas there has been marked progress in reducing gender inequalities, especially in access to education, the participation of female learners and teachers in science is still a subject of concern. For example, findings from a recent study by APHRC on gender mainstreaming practices in basic education and teacher training in Kenya highlighted critical gaps in the participation of female learners and teachers in STEM subjects and leadership. The study covered 250 schools and 4,662 learners in 10 Counties.

Proportion of female teachers in STEM

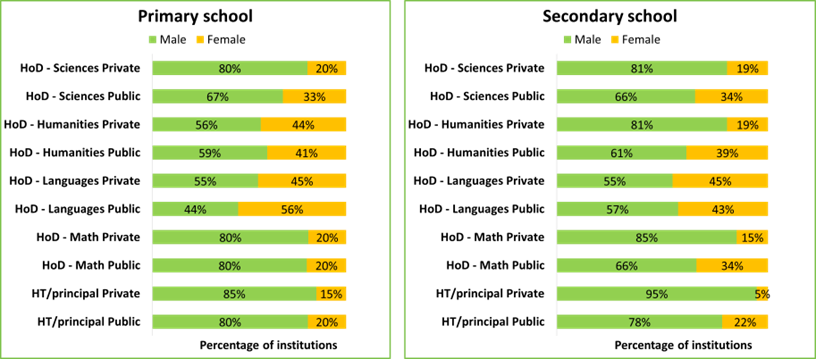

The study findings highlighted that there were proportionately more male teachers as department heads in all subject areas, especially in mathematics and sciences for both primary and secondary schools. For instance, 80% and 85% of mathematics department heads were male at public primary and private secondary schools, respectively. This gender gap was significantly reduced for humanities and languages, with the proportion of female teachers as department heads increasing.

Female preference for STEM subjects

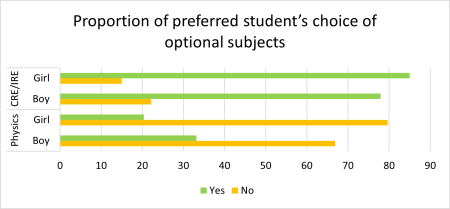

In the Kenyan 8-4-4 curriculum, learners in secondary school are required to undertake all subjects in the first two years (forms 1 and 2) and then select optional subjects that they would like to pursue in forms 3 and 4. The study thus sought to understand the preference of male and female learners to select STEM vs. humanity-related subjects. A significantly lower proportion of girls (20%) reported that they did not intend to choose physics as compared to boys (33%). Additionally, a significantly higher proportion of girls than boys intended to select Christian/Islamic religious education as an optional subject in the future, at 85% and 78%, respectively.

So why the gender disparities

One of the key reasons explaining the gender disparities in the participation of female learners and teachers in STEM is the negative gender-stereotypical threat that STEM subjects are the preserve for boys and men while girls and women excel in languages and humanities. Unfortunately, research evidence shows that this stereotypical threat begins in the early learning years and is persistent into adulthood, thus affecting education and career decisions. For instance, young children learn to attribute masculine traits to science and consequently associate scientists with men. Other studies highlight that students are more likely to associate mathematics and sciences with male teachers. These stereotypes persist in adulthood, where fewer women pursue STEM courses in higher education.

The study by APHRC also showed that these gender disparities are propagated by teaching practices inside the classroom. For example, the classroom observation findings indicated that secondary school teachers engage male learners more than female learners in Mathematics, English, and Science classroom activities.

Call for action

These study findings highlight that even as we celebrate the reduced gender gap in access to education, there is need for concerted efforts to have targeted interventions to enhance the participation of female learners and teachers in STEM. One way would be for both program and policy actors to develop strategies to eliminate negative stereotypical threat, which is one of the biggest hurdles to gender-equitable participation in STEM. However, the government should implement the selected strategies early enough, considering gender stereotypes begin early in life. In addition, experts should review the teacher-training curriculum to ensure it observes gender-responsive teaching strategies.