Guest post by Anrudh K. Jain, Ph.D., Distinguished Scholar, The Population Council. First published on www.champions4choice.org

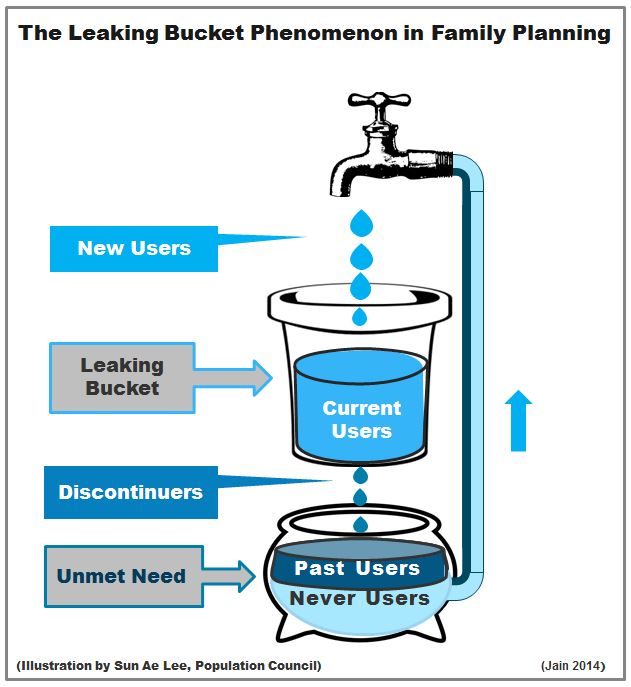

Family planning (FP) programs in developing countries have been experiencing a phenomenon that I like to call “the leaking bucket.” Let’s say that you place a bucket under an open tap and watch the water level rise, until you discover a hole in the bottom of the bucket. Water is now leaking out of the bucket. Filling the bucket will be easier once the hole is plugged. In the same way, meeting women’s desire to reduce unwanted fertility will become easier once FP programs pay more attention to contraceptive discontinuation.

FP programs aim to reach women who want to regulate their fertility, but are not using contraception. Most programs address this “unmet need” by helping these women to initiate contraceptive use—opening the tap to fill the bucket with water. Fewer programs pay attention to women’s reproductive health (RH) needs once they begin using a method. It is important to do so because these women have already overcome all of the well-known barriers to FP use—distance, cost, partner/ family objections, and fear of side effects. These new users have joined the pool of current users; they are the water in the bucket.

Yet many users of reversible contraception stop using their method (become discontinuers) and leave the pool of current users, just like the water leaking through the hole in the bucket. High discontinuation of these methods, observed in many developing countries, may reflect limited contraceptive choice available to women or an infringement on their reproductive rights. Some may not have received their method of choice, while others may not have received accurate information about the anticipated side effects or how to manage them. Some women discontinue the method in order to get pregnant, while others experience infecundity or menopause.

Still, many women stop using a contraceptive method but remain interested in regulating their fertility (past users with an unmet need). Some may not have access to another method, while others may not have been told about other methods or the possibility of switching. These past users join women who have never used a method and who also have an unmet need. Over time, among those with an unmet need, the number of past users could exceed the number of never-users, thus making it difficult to reduce unmet need without helping such women to restart contraceptive use. For example, 82% of women with an unmet need in the Dominican Republic and 74% in Bangladesh in 2007 had used a method in the past but were not using one now.

The “leaking bucket” analogy draws attention to a strategy to reduce unmet need that focuses on the RH needs of women who have already adopted contraception. FP programs need to empower these women to continue using contraception, thereby plugging the hole in the bucket and allowing the water level (the pool of contraceptive users) to rise faster. Consequently, the pool of women with unmet need will shrink as well.

In the same way, the FP2020 goal to reach 120 million women with an unmet need by the year 2020 is more likely to be achieved once donors and FP programs focus on reducing high rates of discontinuation. A 2013 analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data from 34 developing countries indicated that high contraceptive discontinuation in the past coupled with continuation of this trend in the future could contribute up to 94 million former users to the pool of women with an unmet need:

- About 38% of women with an unmet need had used a modern method in the past. This means that of the 120 million women with an unmet need, about 45 million have experience with using a modern contraceptive method.

- About 19% of women who have ever used a modern method discontinued its use, but continued to have an unmet need. Continuation of this trend implies that as many as 49 million out of the 258 million women currently using modern contraception could stop doing so in the coming years and thus join the pool of women with an unmet need.

Past users not only contribute to unmet need; they also contribute substantially to the number of unwanted pregnancies. A 2014 analysis of panel data from two surveys conducted three years apart showed that about 17% of women from 14 Pakistani districts that were using a modern or traditional method at the beginning of the study period subsequently had an unwanted birth. Furthermore, about 37% of unwanted births that occurred to all women during this period occurred among those who started using a contraceptive method but discontinued its use.

Unmet need and unwanted fertility can certainly be reduced to some extent if FP programs help women to initiate contraceptive use (new users), but they can be reduced even faster if programs also empower those already using FP to achieve their reproductive intentions by continuing contraceptive use irrespective of the method they choose.

How can the hole in the leaking bucket be plugged? Contraceptive discontinuation, and consequently unmet need and unwanted fertility, can be reduced by:

- Expanding women’s choice of methods by increasing access to those not currently available in a country;

- Helping women to select the method most appropriate to their current reproductive needs and circumstances;

- Providing women with accurate information about the method they select (e.g., how to use it, anticipated side effects, and how to manage them, if they occur);

- Encouraging women to switch methods (and facilitating switching) as their reproductive needs, circumstances, or method preferences change over time; and

- Stressing the importance of reducing and eliminating the gap between method use to avoid unwanted births.

The issue is not only about adding methods to the contraceptive mix in a country or improving the quality of counseling per se. Rather it is about meeting women’s reproductive health needs, their right to have a choice among contraceptive methods, their right to make informed choices, and their right to receive accurate information from service providers about the method they select and about switching methods whenever the initial one is no longer suitable.