By Shawn Donnan via Financial Times

We are living through the era of Big Data with all its promises and consequences. But is the world also splitting into the data “haves” and “have nots”?

That’s the contention of a new report out today from a UN panel of independent experts from academia and business which warns that the world needs to do more to bolster the data capabilities of developing countries in order to fight poverty more effectively.

Among the report’s conclusions:

Major gaps are already opening up between the data haves and have-nots. Without action, a whole new inequality frontier will open up, splitting the world between those who know, and those who do not.

The report was commissioned in August by Ban Ki-moon, the UN secretary-general, as part of the discussions now under way in preparation for the unveiling next year of successors to the Millennium Development Goals. It calls for a major focus of those successors to be on improving access to good data in the developing world and for a new push on giving governments in those countries the tools they need to make informed policy decisions.

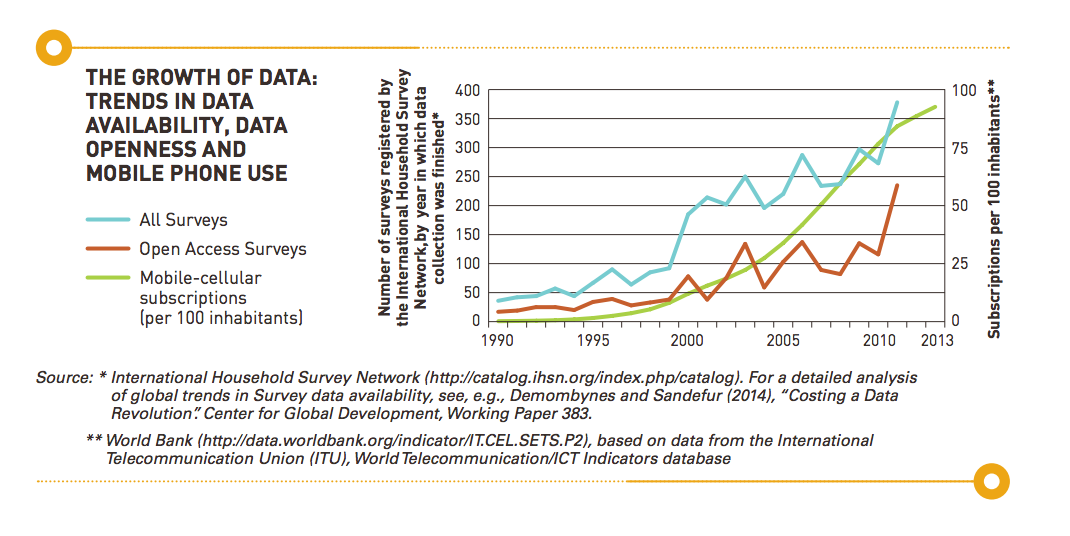

There has clearly been an explosion of data coming out of the developing world over the past 20+ years as part of what has been dubbed a “Data Revolution” thanks to a proliferation of household surveys and mobile phones.

Source: “A World that Counts”, report of the UN Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development. Click to enlarge

But much of the data, the report argues, is too poor to be useful and too slow to arrive to be helpful in determining policy. And that needs to change.

The risk, argues Enrico Giovannini, a former Italian minister who was one of the panel’s co-chairs, is that the next development goals — now provisionally dubbed the “Sustainable Development Goals” — will repeat the mistakes of the Millennium Development Goals, which have guided policy around the world over the past decade and a half.

Partly because of the lack of technology at the time and greater restrictions on access to data, Prof Giovannini argues, the MDGs both were both informed less by data and monitored less closely than their successors should be.

The question of data and the MDGs is not uncontroversial. It led to a public clash in May between Bill Gates and Jeffrey Sachs after Gates said he and his foundation had declined to invest in Sachs’ Millennium Development Villages because, in part, he questioned how feasible it would be to measure progress in those communities. In a post titled “Why Bill Gates Gets It Wrong” Sachs fired back a few days later that there was plenty of data available on the villages and that a rigorous review would come out in 2015.

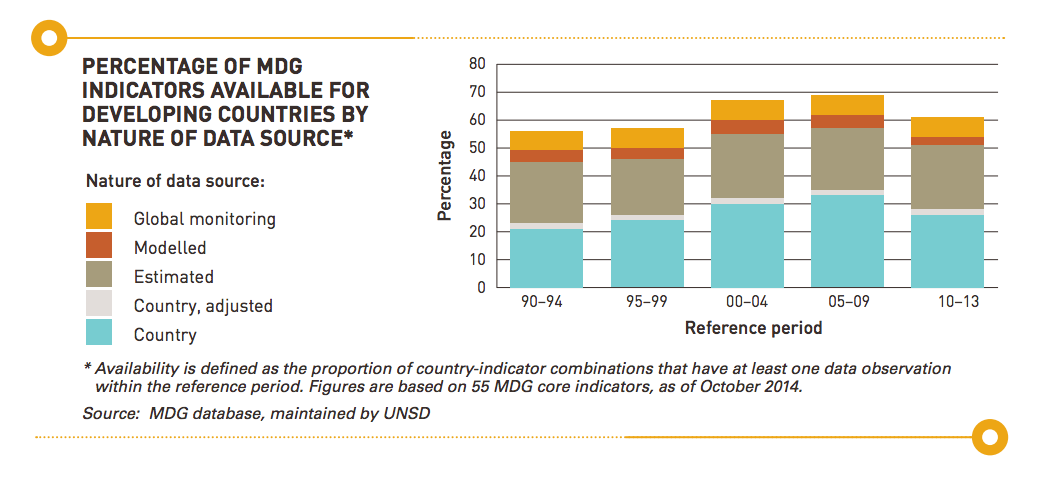

But the new UN report does raise some serious questions about the MDGs and data. The MDGs had spurred “huge investment” in data gathering, the report’s authors write. However, more than a decade after they were set, a lot of data are still missing on the MDGs, the UN expert panel found. As the graph below shows, at best, less than 70 per cent of the data needed is available for certain periods. And a huge portion (the tan section of the bars below) is simply “estimated” data.

Source: “A World that Counts”, report of the UN Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development. Click to enlarge

Beyond the MDGs there are still “some very basic data gaps” in many developing countries, says Claire Melamed, a poverty researcher at the UK’s Overseas Development Institute who served on the UN expert panel. In many countries, she points out, basic birth and population data are still not available or collected in a usable form.

“If you don’t know where people live how can you possibly get health services to them?” she asks.

The UN report is not the first to identify the data problem. In July, researchers from the Washington-based Center for Global Development and the African Population and Health Research Center warned that too little reliable data was available on Africa to guide development policy.

In a companion working paper CGD researchers Justin Sandefur and Amanda Glassman warned that official statistics in Africa “systematically exaggerate development progress”. Governments, they found, often misreported basic data on things like vaccination rates to foreign donors. In the case of primary education in Tanzania, they found, while official government statistics showed the country was on the verge of reaching the goal of universal primary education, household surveys actually showed 1 in 6 children aged 7-13 were not in school.

Having good data matters, as the authors of the new UN report write.

Data are the lifeblood of decision-making. Without data, we cannot know how many people are born and at what age they die; how many men, women and children still live in poverty; how many children need educating; how many doctors to train or schools to build; how public money is being spent and to what effect; whether greenhouse gas emissions are increasing or the fish stocks in the ocean are dangerously low; how many people are in what kinds of work, what companies are trading and whether economic activity is expanding.

Without good data the risk is that even as Big Data improves the lives of people in the rich world, not having the same access could well prove yet another source of impoverishment and rising inequality for those in the developing world.

Cross posted from http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2014/11/06/inequality-and-why-the-worlds-poor-are-being-left-behind-by-big-data/